Let’s talk about some of our blind spots related to decarbonization.

Now, what does one have to do with the other, you may ask. Good question. We often hear that a climate-safe future is a necessary condition for peace. That’s true. We also often hear that renewables could be the energy of peace. Less true. To understand, I need to tell you about the materials that we need in order to decarbonize. They’re pretty. And they can be deadly. Looking into their story tells us that confronting conflict and building new forms of international peace are going to be critical foundations to build a climate-safe future

Contents

We need to recouple economic growth with intensive mineral extraction

So let me tell you about them, starting with where we stand now. When we talk about a decarbonized future, we generally have in mind the possibility of decoupling economic growth from greenhouse gas emissions. That’s what we call “green growth.” What we tend to think about less often is that to get there we need to recouple economic growth with intensive mineral extraction.

To harness renewables or renewable energy like the sun and the wind, we obviously need to build technologies such as solar panels, windmills, batteries, right? And to build those, we need to mine huge quantities of non-renewable materials such as these. Knowing that it takes mines as big as these to produce that much amount of usable material. Our ticket to green growth, in other words, is digging deep in the environment.

Now we know that mining can have grave impacts for local ecosystems and populations. I’ve seen it myself, and it really isn’t pretty. But what I want to talk about today is about how much and where we’re going to have to dig, and what that means for planetary security and for geopolitics.

When the dominant source of energy changes, power relations change as well

I’ll start from there. History tells us that when the dominant source of energy changes, power relations change as well. Countries that can transform energy to their own advantage, can gain the upper hand economically and politically, and then can put themselves at the center of the global order. Think of the United Kingdom and coal, for instance, or how oil determined the ascendance of the US to a global superpower.

What that tells us is that the access to and processing of energy literally materializes into the ability to shape geopolitical power dynamics. And today, we’re facing the challenge of implementing the biggest energy transition in the history of humankind under a ticking climate clock. The race is on for a new generation of power. At the heart of which you have all of the critical materials that we need to decarbonize on the one hand and digitalize on the other.

The future is going to be more materially intensive than before

So what’s happening with them? On the demand side we’re at the beginning of an exponential demand curve. If you take lithium as a proxy, a key component for [batteries], global production already increased by just short of 300 percent between 2010 and 2020. I’m going to pause here for a sec. This is really good news. It means that decarbonization is in motion.

The not so good news is that our “clean” future is going to be more materially intensive than before. If you take a simple measure for it, the International Energy Agency tells us that with the current level of innovation, an electric car requires six times more mineral inputs than a conventional car! And this is only the start. The World Bank tells us that with the current projections, global production for minerals such as graphite and cobalt will increase by 500 percent by 2050, only to meet the demand for clean energy technologies.

Dominate of China

Now let’s look on the supply side. That’s where a lot of really interesting things are happening. Who currently exploits and processes minerals and where deposits to meet future demand are located tell us exactly how the transition is going to change geopolitics. So if you look at a material such as lithium, countries like Chile and Australia tend to dominate extraction while China dominates processing. For cobalt, the Democratic Republic of Congo dominates extraction while China dominates processing. For nickel, countries like Indonesia and the Philippines tend to dominate extraction, while China, you guessed it, thank you, dominates processing. And for rare earths, China dominates extraction while China dominates processing.

I’ve just said China a lot, didn’t I? Well, that’s because China skillfully leveraged its geo-economic rise to power over the last two decades on the back of integrating supply chains for rare earths from extraction to processing to export. We tend to point fingers at China today for not going fast enough on its own domestic energy transition, but the truth is that China understood already long ago that it would play a central role in other countries’ transitions. And it is. The European Union, for instance, is 98 percent dependent on China for rare earths. Needless to say, this puts China in a prime position to redesign the global balance of power.

Now, you may argue that this is a good thing because the global balance of power needs a rehaul anyway. And you know what? I can totally roll with that. But – and this applies to China, the United States, and any other big player – we need to make sure that the redesigning process doesn’t compromise on human rights or open societies. And that it doesn’t lead to the weaponization of supply chains at a time of international instability, and more importantly, at a time of complete climate breakdown. Unfortunately, we’re already seeing signs of this happening.

China is currently trying to gain access to more mineral resources through its Belt and Road Initiative. The United States and Europe are both thinking of reshoring critical mining and processing and orienting some of their international partnerships to facilitate access to more mineral resources. Japan is exploring some of its oceanic marine reserves to build strategic reserves.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

I’m also speaking in the shadow of a war on the European continent. Now at first sight, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has nothing to do with what I’ve been talking about. But Ukraine happens to be mineral rich. It also happens to be one of only two countries that had struck a partnership with the European Union to diversify and develop supply chains for critical raw materials. That partnership was specifically designed to help the EU decarbonize and in the process to better integrate with Ukraine from a political and economic perspective.

Eight months after the partnership was struck, the invasion took place. Now, mineral resources may not explain everything about the war. But they certainly can’t be ignored in analyzing the events. Because when it comes to the race for critical raw materials, what’s actually happening is that we’re headed right back into a new scramble for resources, at the heart of which you find all of the big players eyeing countries with vast mineral deposits.

And yet it’s so obvious many of these countries that are located, for the most part, in Africa, in Latin America, in Central Asia and in the Indo-Pacific. Economists will tell you that this is a great thing, because these countries, or at least a lot of them, need economic resources and many, to accelerate their development pathway and climate adaptation.

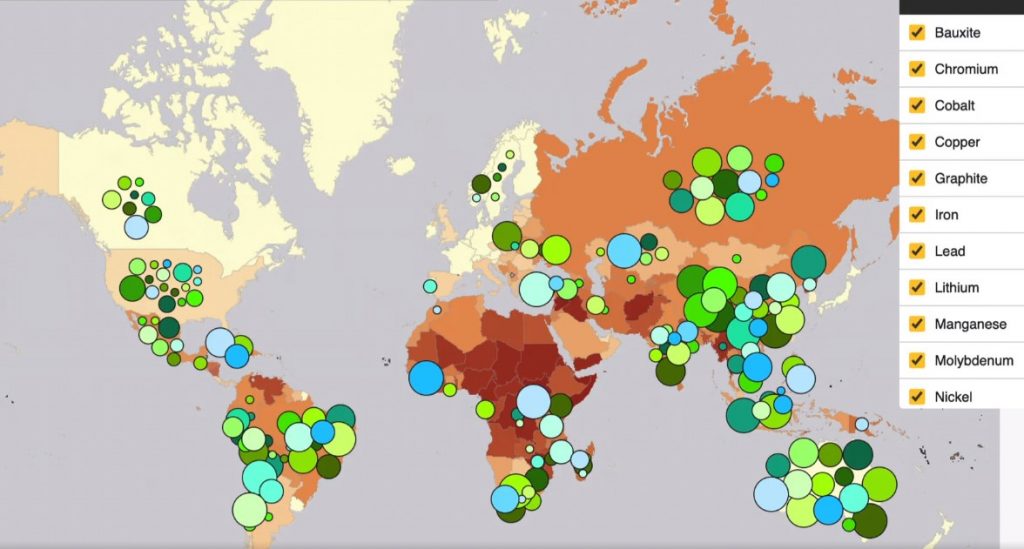

But. Many of these countries also have very real overlapping risk profiles. The International Institute for Sustainable Development first produced this map back in 2018. Can you see the green dots on the map?

They represent all of the different materials that we need in order to decarbonize, their geographic location and their deposit size. As it so happens, a lot of the deposits are located in countries that rank fairly high on corruption indices. They are represented essentially by the shades of brown and red on the map. And as it so happens, a lot of the materials are also located in countries that are fragile, such as Sri Lanka, or downright conflict affected, like Myanmar and the Central African Republic.

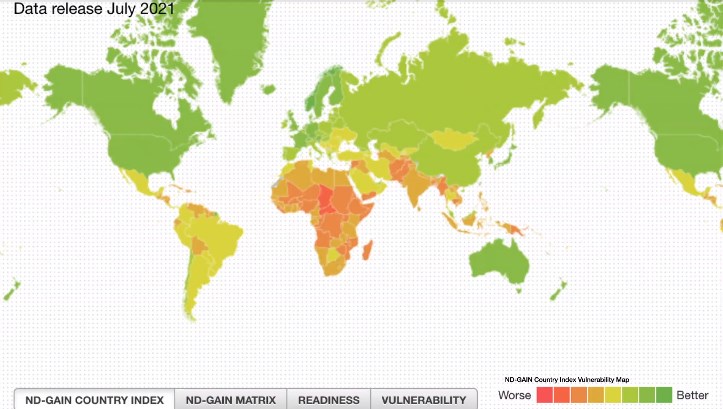

That’s not all. The Notre Dame Institute tells us, with this map, in which you see, again, some red and orange, that countries that are climate vulnerable are also the ones that are resource endowed.

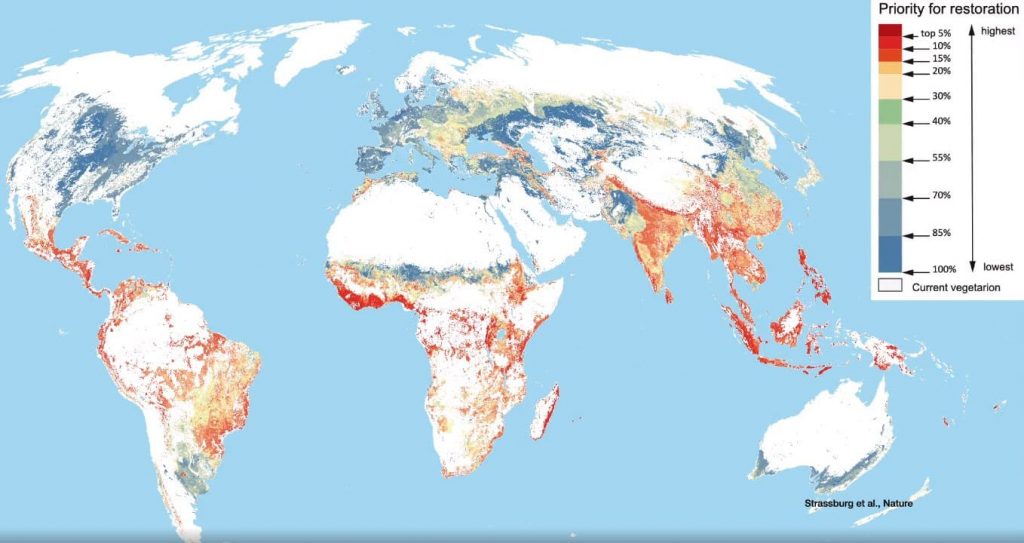

And one final thing. You know those big ecosystems that we need to protect and regenerate in order to stabilize the global climate regime? To reboot the hydrological cycle and to protect biodiversity? They’re also represented in orange and red on this map. Many of these big ecosystems are located in the same fragile countries that I was mentioning before. They also happen to sit on vast mineral deposits. Changing or eliminating these ecosystems through mining, through deforestation or anything else would undermine planetary security. Not just international security. Planetary security.

It’s essentially like a perfect storm in the making. Corruption, institutional and socioeconomic fragility, climate disruptions and environmental plundering, all acting as a backdrop to a competition to gain access to the minerals that we need in order to decarbonize. All of these factors will be magnified if we don’t rein in the scramble for resources. All of them will reinforce one another.

And I want to make something very clear here. The countries at the heart of the resource scrambling may suffer the most direct consequences in terms of their ability to develop, to adapt to climate change and to avoid violence. But their fate is not isolated. Their problems are not geographically distant. Our big blind spot here is that we’re headed towards a decarbonization trajectory that may end up undermining ecological integrity and heighten the risks of conflict and insecurity whose consequences would reverberate worldwide.

What we need to build peace

I know that this is not a particularly encouraging picture. And that it comes on top of layers of pictures that are not particularly encouraging. Our modern economies have advanced and grown for two centuries through the gigantic blind spot of fossil fuel exploitation and its unintended consequences. The big lesson here is that we can’t afford to just shift to a different set of energies, technologies and materials without paying attention to the unintended consequences. The stakes are too high. They involve our future. That we know. But they also involve our humanity. And they involve our nature, by which I mean the nature that we choose for ourselves.

Decarbonization is the way forward. There’s not one single doubt allowedd about this. But the way forward also demands of us that we start imagining our future beyond decarbonization already. Remember what I said at the beginning? A climate-safe future is a necessary condition for peace. But we won’t achieve a climate-safe future without peace. And to build peace, we need to shake things up in international politics and in the way that we do business and economics. So where do we start? I’d like to offer the scaffolding of a plan in four different baskets.

First, science. Science can tell us exactly where it is safe to mine and where it isn’t, from an ecological perspective. Where it is not safe to mine, we need to act as though these minerals did not exist and establish protected areas under which no mining licensing can take place. Where mining does take place, we can integrate socioeconomic and ecological regeneration within business models.

Second, a global public good regime. If decarbonization is a matter of human survival, then the materials that we need in order to decarbonize should be managed collectively under a global public good regime. The alternative is conflict and planetary breakdown. So while we figure out exactly how to design this regime, the countries at the heart of the scramble for resources should receive adequate support, competent and coherent support to face off the joint challenges of geopolitical competition and climate disruptions on the other hand. In other words, investing into conflict resolution, into the fight against corruption and into context-specific resilience, should be top priorities of our global energy transition.

Third, changing the way that we do business and economics. We can’t just switch from one energy system to another. I’ve made that pretty clear, right? What we need instead is to reduce our need for energy and for materials. And that starts with massive public and private investments into circular economic models that favor recyclability and material substitution.

Now, here’s the thing. We know that this is a necessary step, but not a sufficient one. So what we also need to do is to develop ecological assessments for supply chains that account for greenhouse gas emissions, but also for water, soil, biodiversity, material and energy footprint all at once. Only on this all-encompassing basis will we understand how supply and distribution chains need to change and therefore how globalization needs to transform.

Fourth, innovation. All of this can only happen if we start shifting our thinking about innovation. Innovation in our times is about bringing back economic footprint within planetary boundaries. Anything else, even the coolest of new products, if it isn’t aligned with that goal, it’s not innovation, it’s business as usual. In our little corner of the world, my team and I at Carnegie Europe have been working really hard to identify what regenerative foreign policy looks like and what it aims for.

There are two things that we know by now. One is obvious, we need to tackle fundamental issues around economic redistribution on a global scale. The other thing is that we need a geopolitical de-escalation around decarbonisation and regeneration. We’ve translated that into a concept we’ve called ecological diplomacy. And we’re pushing really hard for the European Union to adopt this framework within their foreign policy.

Because if there is one thing that we’ve understood, it’s that ecological integrity is the foundation for all types of security. Which makes it the one common denominator that we can work on rebuilding collectively. And we can manage. Truly, I believe that we can. As long as we shed light on our transition blind spots and take them as our guiding companions to identify what truly systemic, truly peaceful and truly safe solution pathways look like for the age of climate-disrupted futures.